Projects

What happens when the left side of the heart doesn’t grow?

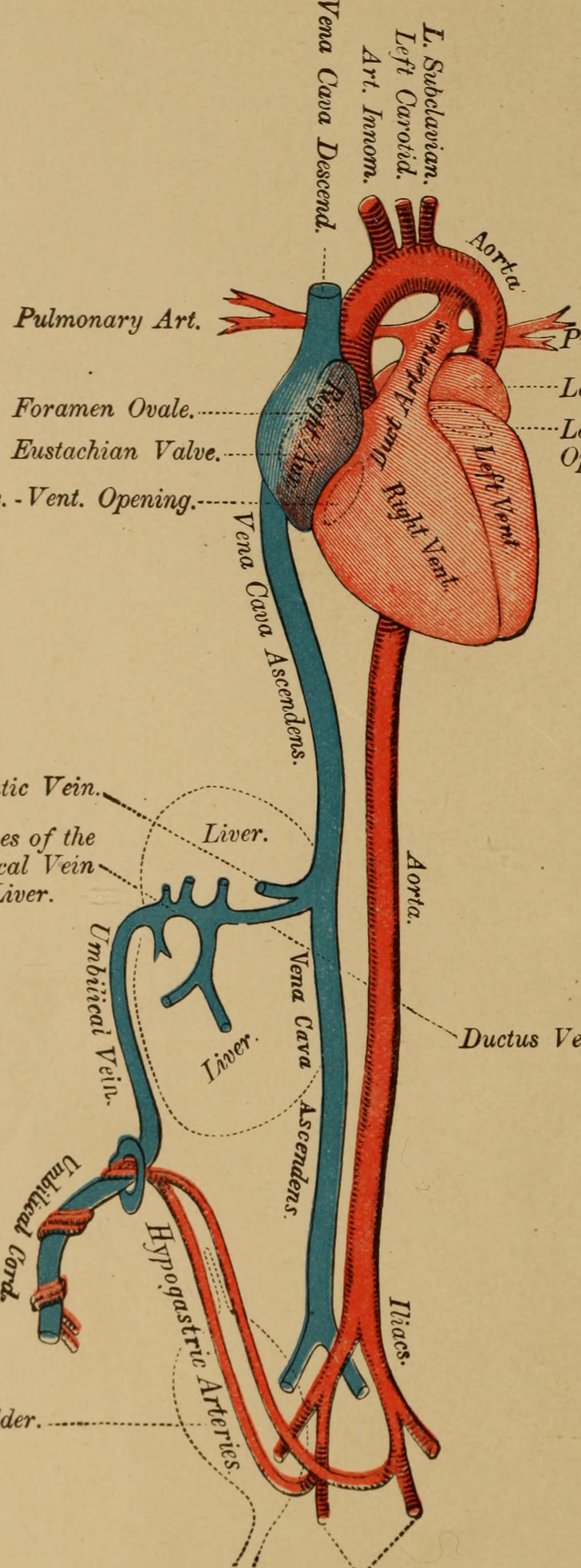

Normally, the left side of the heart pumps blood to the body but sometimes, during fetal development, the left ventricle doesn’t form properly. When this happens, the heart relies entirely on the right ventricle to do all the work. The right side is usually responsible for pumping blood to the lungs after birth. In babies born with a severely underdeveloped (or “hypoplastic”) left heart, a series of complex surgeries soon after birth to permit the right ventricle to pump blood to the body can be life-saving.

But the right side of the heart isn’t built to pump blood to the body for a lifetime — and that difference matters. These individuals are at higher risk for heart failure over time.

Our research asks: How does the added work in fetal life affect how the right ventricle develops? Does it trigger the heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) to grow more? Or to mature faster and stop dividing too soon? Do the cells simply get bigger? How do these differences impact heart function? And how are the developing organs, which rely on that blood flow, affected?

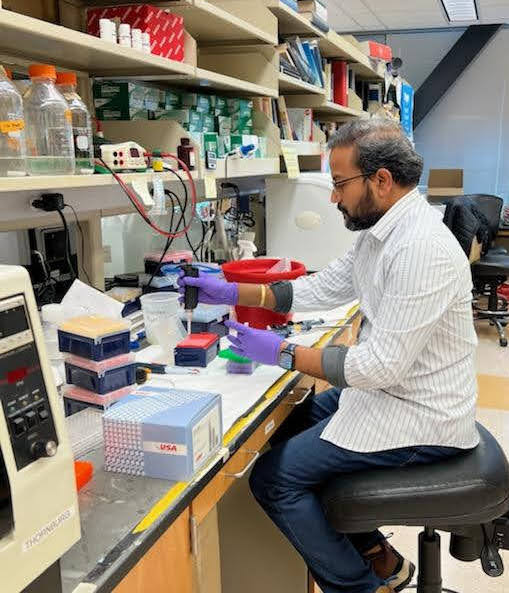

We’re using fetal sheep to study these questions to better understand this complex condition and improve outcomes for children and families facing it.

Publications

Hagen MW, Louey S, Alaniz SM, McClellan EB, Lindner JR, Giraud GD, Jonker SS. Enhanced myocardial perfusion in late gestation fetal lambs with impaired left ventricular inflow. J Physiol. 2025 Feb;603(4):971-987. doi: 10.1113/JP286685.

Onohara D, Hagen M, Louey S, Giraud G, Jonker S, Padala M. Chronic in utero mitral inflow obstruction unloads left ventricular volume in a novel late gestation fetal lamb model. JTCVS Open. 2023 Oct 4;16:698-707. doi: 10.1016/j.xjon.2023.09.036.

The cells that shape a strong heart

Your heart’s strength depends a lot on how many muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes, you start with at birth. These cells help your heart beat for a lifetime. But there’s a catch: after birth, your body makes new ones very slowly. And as you age or when your heart is stressed, many of these cells die.

That means the number you’re born with really matters, especially if you have heart disease. In fact, how your heart grows before and just after birth can shape your health for the rest of your life.

We’ve discovered something surprising: right before birth, a big wave of cardiomyocytes die off. Why would that happen just as a baby is about to begin life outside the womb? And importantly — can we stop it?

We’re using sheep to help us find the answers. We can’t easily study heart muscle cells in human babies, but sheep hearts grow in similar ways. By learning why these cells die and how to protect them, we hope to find new ways to support babies born with heart conditions and give them stronger starts.

Publications

Jonker SS, Louey S. Fetal cardiac troponin I levels decline toward birth in sheep. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2024 Jun 1;326(6):H1538-H1543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00224.2024.

Bose K, Espinoza HM, Louey S, Jonker SS. Sensitivity and activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response and apoptosis in the perinatal sheep heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2024 Jul 1;327(1):H1-H11. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00043.2024.

Jonker SS, Louey S, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL, Faber JJ. Timing of cardiomyocyte growth, maturation, and attrition in perinatal sheep. FASEB J. 2015 Oct;29(10):4346-57. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272013.

How the fetal heart responds to fat

Before birth, a fetus gets all its nutrients from the mother through the placenta. At that time, fat levels in the fetus’s blood are very low. Instead of using fat for energy, the fetal heart relies mostly on carbohydrates like glucose and lactate.

After birth, things change quickly. Babies begin nursing, and the amount of fat in their blood increases. The heart adapts and begins using fat as a major energy source. To do this, heart muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes, need to change how they function.

Here’s what’s interesting: high levels of fat can be toxic to cardiomyocytes. Yet these immature cells seem ready to handle fat even before birth. So how do they prepare to start using it safely for energy?

We’re studying this transition using animal models. Understanding how the heart makes this switch could help us support babies, especially those with heart conditions, as they adjust to life outside the womb.

Publications

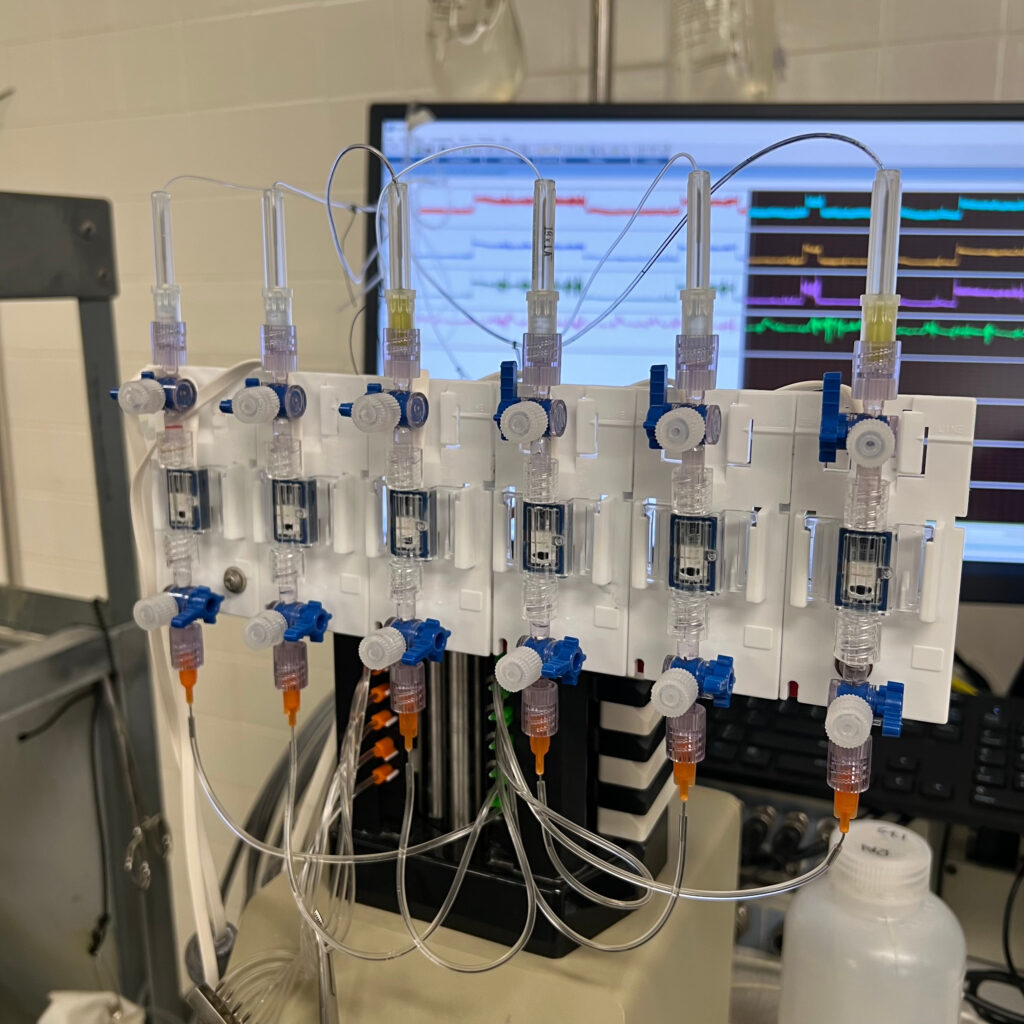

Barooni N, Chen A, Alaniz SM, Minnier J, Louey S, Jonker SS. Physiological response to fetal intravenous lipid emulsion in mid-gestation. Clin Sci (Lond). 2025 Sep 24;139(18):997-1013. doi: 10.1042/CS20256946.

Iverson K, McClellan EB, Jonker SS, Louey S. Myocardial growth response to fetal intralipid infusion in sheep. FASEB J. 2025 Aug 15;39(15):e70911. doi: 10.1096/fj.202501607R.

Piccolo BD, Chen A, Louey S, Thornburg KLR, Jonker SS. Physiological response to fetal intravenous lipid emulsion. Clin Sci (Lond). 2024 Feb 7;138(3):117-134. doi: 10.1042/CS20231419.

Chattergoon N, Louey S, Jonker SS, Thornburg KL. Thyroid hormone increases fatty acid use in fetal ovine cardiac myocytes. Physiol Rep. 2023 Nov;11(22):e15865. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15865.

The connection between muscle and blood supply

Muscle cells need a lot of energy to do their job. In the heart, that energy comes from oxygen and nutrients delivered by the blood. Waste is also carried away by the blood. This exchange happens at the smallest blood vessels, called capillaries.

When heart muscle cells don’t get enough blood, they start to struggle. They can’t contract or relax as well, they become less responsive to insulin (a sign of pre-diabetes), and they can even die. How well capillaries grow during fetal life and early infancy plays a big role in how healthy the heart stays over a lifetime.

But what happens when the environment in the womb changes how the heart muscle grows? Does the growth of capillaries keep up, slow down, or change in another way? And does that mismatch last or does the heart find a way to fix it?

We’re studying these questions to better understand how early life shapes the health of the heart’s own blood supply and how that might help prevent heart disease later in life.

Publications

Hagen MW, Louey S, Alaniz SM, McClellan EB, Lindner JR, Giraud GD, Jonker SS. Enhanced myocardial perfusion in late gestation fetal lambs with impaired left ventricular inflow. J Physiol. 2025 Feb;603(4):971-987. doi: 10.1113/JP286685.

Hagen MW, Louey S, Alaniz SM, Belcik T, Muller MM, Brown L, Lindner JR, Jonker SS. Changes in microvascular perfusion of heart and skeletal muscle in sheep around the time of birth. Exp Physiol. 2023 Jan;108(1):135-145. doi: 10.1113/EP090809.

Hagen MW, Louey S, Alaniz SM, Brown L, Lindner JR, Jonker SS. Coronary conductance in the normal development of sheep during the perinatal period. Physiol Rep. 2022 Dec;10(23):e15523. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15523.